I accept it is my job to try and engage the younger generation and try to do this with school visits, question times, public meetings, the charity walks and so much more. But all better ideas accepted.

I agree that political engagement – or the lack of it – is once again in the news, with Thursday’s Panorama programme adding to the general cynicism and last Sunday’s Observer opining that ‘democracy, far from flourishing, is sicklier than ever’.

Full details of the blog and the work of the NFER here: http://thenferblog.org/2013/06/05/why-politics-must-appeal-to-the-facebook-generation/

Lack of engagement among young people is one strand in this general malaise, and on this issue we at NFER have evidence from a fascinating series of surveys that tracked a cohort of young people from when they started their citizenship education at the age of 12 in 2002, to 2011, when they had had the chance to vote in the 2010 election. It is from this 2011 survey, which included 1500 young people, that we gained a wealth of insights into the views of young voters. The initial signs were not encouraging: only 59 per cent of our sample actually voted, and 79 per cent of respondents had little or no trust in politicians.

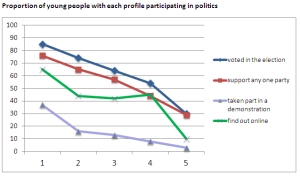

We were interested to find out whether there were patterns of responses that could identify distinct groups of young people in respect of their political views and involvement. When we applied statistical techniques to this question, five such ‘profiles’ emerged, ranging from highly engaged to uninterested. More about these profiles can be found in the full paper but for the current debate, it is the difference between traditional and online involvement in politics that offers some interesting possibilities.

Of our five profiles, only the highly engaged group – about one-fifth of the sample – are at all likely to take part in traditional means of political involvement such as meetings, demonstrations or writing to an MP. There are three groups in the middle with different levels of partial engagement, who are generally not interested in getting involved in traditional ways – but who are much more active online. When asked how often they ‘Find out about social and political issues from Facebook or Twitter’, over 40 per cent of these partially engaged groups said they do this at least once a week. Over 40 per cent of these groups also say they have signed online petitions.

The graph illustrates how online involvement contrasts with traditional modes. The ‘highly engaged’ group is labelled 1 and these young people have active involvement of all kinds. Groups 2, 3 and 4 have declining levels of traditional involvement, but their online participation holds up much better. This means that about four-fifths of young people may be open to exploring social and political issues online, in contrast to the one-fifth who may be motivated to attend meetings or demonstrations.

What can traditional politics do to reach out to this generation of voters whose natural source of information and means of communication and debate is online? Viewed in this way, the evidence suggests that a wholesale shift to new media is needed for younger people. If hustings, debates and arguments were conducted online, and if voting itself was online, new ways of building support could emerge. But in light of the prevailing mistrust, it seems that some bold and imaginative thinking is necessary to make